History of the Underground Railroad: A Timeline

by Fergus M. Bordewich

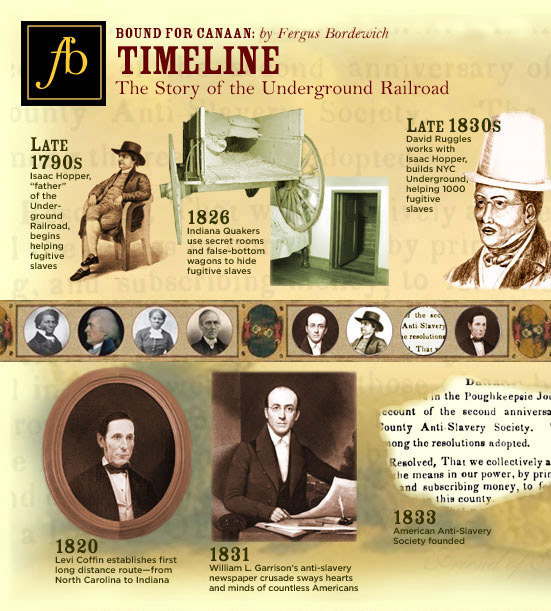

- LATE 1790S: Quaker Isaac T. Hopper and African-American collaborators begin helping fugitive slaves in Philadelphia. Their cooperation set the pattern for the Underground Railroad.

- 1820: Vestal and Levi Coffin send fugitive slaves overland with Quaker emigrants from North Carolina to Indiana, establishing the first long distance route of the Underground Railroad.

- 1826: Levi Coffin moves to Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana. There he establishes one of the most effective underground operations in the trans-Appalachian west. Fugitives are sometimes carried in false-bottomed wagons, or hidden in secret rooms.

- 1831: William Lloyd Garrison establishes the Liberator, in Boston. It is the first newspaper to call for the immediate abolition of slavery. Garrison’s passionate advocacy will sway the hearts and minds of countless Americans.

- 1833: The American Anti-Slavery Society is founded in Philadelphia, at the first national conference of abolitionists in American history. Many members of the society will become activists in the Underground Railroad.

- Late 1830s: David Ruggles creates the African-American underground in New York City. He will help more than one thousand fugitive slaves. One of his closest collaborators is Isaac Hopper.

- 1840: The World’s Anti-Slavery Convention is held in London, England. Among the American delegates is underground activist and lifelong abolitionist Lucretia Mott. Her husband James presides at the conference.

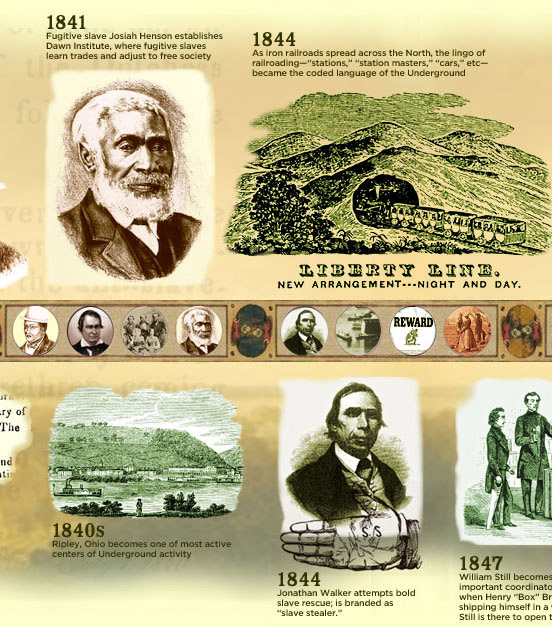

- 1840s: Fugitive slaves escape in growing numbers across the Ohio River. The family of Rev. John Rankin helped to turn Ripley, Ohio into one of the most active centers of underground activity.

- 1841: Fugitive slave Josiah Henson establishes the Dawn Institute near Dresden, Ontario. One of several model communities established in Canada, its goal is to educate fugitive slaves in useful trades, and to help them adjust to life in a free society. It is also a terminus of the Underground Railroad.

- 1844: The earliest representation of the Underground Railroad as an actual train appears, in an abolitionist newspaper in Illinois, the Western Citizen. As iron railroads spread across the North, the lingo of railroading— “stations,” “station masters,” “cars,” and “passengers” —became the coded language of the underground.

- 1844: Jonathan Walker attempts one of the boldest slave-rescues on record. He sets off with six fugitives in a small boat from Pensacola, Florida bound for the British Bahamas. They are captured just one day’s sail short of their destination. Walker is branded with the letters “SS” for “slave stealer.” Later, he proudly proclaims that they stand for “slave savior.”

- 1847: William Still is hired as a clerk by the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. He soon becomes the coordinator of one of the most important underground networks in the country, linking activists from Norfolk, Virginia to New York, and throughout southern Pennsylvania. When Henry “Box” Brown succeeds in one of the most dramatic fugitive slave escapes, in 1848, Still is on hand to help open the box. Brown had himself shipped from Richmond, Virginia to Philadelphia in a box.

- 1848: Thomas Garrett, one of the underground’s most important station masters, is put on trial in Wilmington, Delaware for helping the escape of six fugitive slaves. After his acquittal, he defiantly declares that he will add another story to his home to accommodate more fugitives. The first national women’s rights conference is held in Seneca Falls, New York. Women have long been active in the underground. Increasingly, they identify their own oppression with that of slaves.

- 1849: Harriet Tubman escapes from slavery in Maryland. She will return to Maryland at least thirteen times to rescue slaves, and guide them to safety in the North, becoming the most famous “conductor” on the underground. Thomas Garrett and William Still will be among her closest collaborators.

- 1850: Congress passes the Fugitive Slave Act. The law requires all citizens regardless of their personal beliefs to collaborate with public officials in capturing and returning fugitive slaves to their masters. Protests against the law erupt across the North. Recruits flock to help the Underground Railroad.

- 1851: Abolitionists confront federal officials and slave hunters in a wave of violent resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act. African-American underground activists fight off slave-catchers at Christiana, Pennsylvania, killing slave owner Edward Gorsuch.

- 1852: Isaac T. Hopper, the “father of the Underground Railroad,” dies in New York.

- 1853: In many parts of the North, the Underground Railroad has become increasingly open, as Northerners refuse to cooperate with Federal officials. In Detroit, Michigan, Albany, New York, and elsewhere, underground activists openly advertise their work with fugitives.

- 1850s: Fugitive slaves in Canada number more than 20,000. Communities mature and prosper. Fugitive slave, underground activist, and journalist Henry Bibb establishes the Voice of the Fugitive, which reports details of fugitives’ arrivals in Canada. His rival, Mary Ann Shadd, the daughter of an underground station master, becomes the first black woman to publish a newspaper in North America.

- 1859: John Brown captures the federal armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Among his men is a fugitive slave from South Carolina, Shields Green. He dreams of extending the Underground Railroad into the Deep South via a chain of armed posts in the Appalachian Mountains. Brown and his men are captured and executed.

- 1861: South Carolina troops fire on Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor. The Civil War begins.

- 1861-1865: The Underground Railroad is superseded by the Civil War. Wherever Union armies march, slaves flock to their protection.

- 1870: The Fifteenth Amendment extends suffrage to African-Americans. Underground veteran Levi Coffin proclaims that the underground has reached its symbolic end. “Our work is done,” he declares.